Back in April, we stayed at home while the schools were out – everywhere is too crowded for a visit, and places tend to run events aimed at those with the reading ability and attention span of a five year old child. Our first day out in April was to Sutton Hoo. At the time, I was still stunned by the sudden death of our youngest cat and wasn’t in the mood to write about it.

Looking forward now to our third visit to Sutton Hoo, I’m ready to write about my first two visits. I passed the sign for Sutton Hoo at least fifty times in the last twenty years, and every time I thought; “Not now, I’m just keen to get home before the rush hour” or “They’ll be closed by now” or “One day.” The visit in April was after the long lockdown for Covid and the site’s shutdown for renovation, and was very much anticipated and dreaded. Renovated sites often focus on making the simplest possible display – aimed at children. Guys, we aren’t all three feet tall and obsessed with our own poo.

We turned up early. We had to book a half hour slot of arrival (stay as long as you like), and we chose ten to ten thirty. We were in a queue of maybe twenty cars by 10 am, so it was a great idea of theirs to restrict the numbers arriving in each half hour slot. One of the post-Covid queues apparently snaked out onto the main road outside, through the village and back onto the A12.

We had a dry, sunny day for that first visit. There were women set up outside the cafe and shop building who were demonstrating weaving and sewing skills and in the rush to see everything, I didn’t stop – and I should have done. We’d bought two tickets on the first tour around the mounds at 1 pm, so our first stop was to go up the new viewing tower.

The view from the next to last height looks back across the Deben, the river from which the boat was dragged for the king’s burial. The view from the top is across the field where the mounds are. I got to the edge only by hanging on to the rail hard and resolutely not looking down too often – the flooring is a steel mesh on each floor, which means that you can look down through all the mesh and see who’s walking in at ground level. Then you can hear them as they clang up the steel stairs, and feel the tower vibrate ever so slightly. I am really, really not good with heights. I survived Pulpit Rock in Norway by going no further than the mesh walkway with a 2,000 foot drop beneath it. Which meant I was spared the sight of the people sitting on the edge of the 2,000 foot sheer drop to the fjord, and the total prat who ran from the back right to the very edge to throw a banana off the edge and down into the fjord. Pity any boats sailing below.

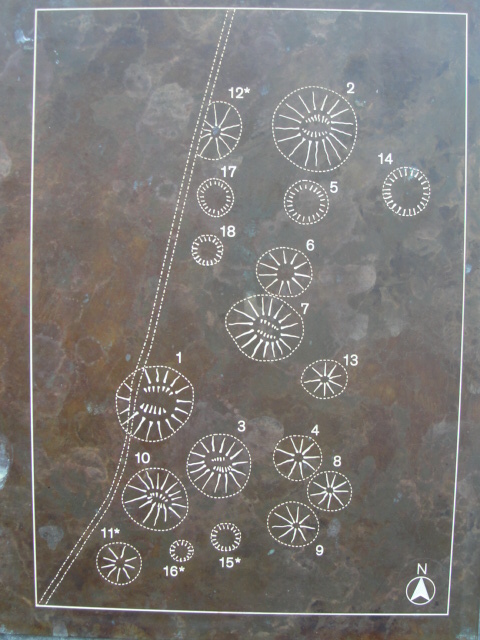

It did give us a great overview of the mounds, with a plate to explain which was which and which had been dug out, robbed, undisturbed. Getting up there early meant we were able to look in peace before the crowds arrived.

Back down. Around the path, away from the approaching crowds and down towards the river Deben. We moored our yacht on the Deben for years, and sailed up as far as Woodbridge (close to Sutton Hoo). There’s a walk that takes you down and along a quiet path and back up a long slope to the cafe. By the time we got there, we really needed a drink and a sit down.

From here, we went back to the gate to the viewing tower where we were met by the guide to the tour of the mounds. Visitors are not allowed to walk across the field of mounds without supervision, and that’s a good thing, considering the thousands of visitors to the site every month. The ground would be worn to bare earth in a very short time.

The tour guide was one of the women from the Sutton Hoo Society, a group of – I think you’d call them re-enactors, though they don’t do battlefields. They weave their own cloth, make their own clothing in the pattern and style of the Saxon age and embroider the edges of their sleeves and hems. Beautifully. She was stately and graceful, reminding me of a senior nun or a lady of a great estate. She took us around the site, explaining the story of the family, the dig and the finds. The group of twenty Dutch teachers who had joined the tour were as fascinated as the rest of us.

She explained that the scattered finds over the years hadn’t gathered enough enthusiasm for a concerted dig until Edith Pretty threw a dinner party, and included a medium among the guests. Mrs Pretty told the guests that she thought the bumps in the field might be burial mounds, and the medium claimed to see a procession of ghostly figures walking slowly from the mounds towards the house. Drama, maybe, but Mrs Pretty took action on this and her own conviction that there was something to be found out there and hired Basil Brown to dig. And the rest is Netflix. Sorry, History.

When the guide reached the mound where the ship was found, she described the discovery of the imprints of ship’s nails before war was declared and the dig closed, resuming after the war finished. Nothing valuable was found – but then, King Henry VIII was known to have sold off the rights to dig out the treasures in sites such as Sutton Hoo, provided he got his commission. There’s no record of exactly what was robbed out.

The tour went to the site where a young warrior was buried with his horse nearby, and I was reminded of the site I’d heard of where a deceased Roman general was placed in his chariot, the horse harnessed to the chariot, driven into the burial pit and then shot and buried in its traces as if the Roman had been frozen at the height of battle.

Finally, the site where a woman of high status lay buried, her name (like the king’s) lost to history. We stayed to see the site where the bodies of criminals had been found, strangled and dumped, and then wandered off to the obligatory visit to the gift shop and the museum.

A fascinating place. I should not have waited so long to visit.